A Life Behind the Lens: Cor Vos x The Handmade Cyclist

Last week we launched Alpe '86, the first super-limited edition tee in our new Top Ten collection, featuring iconic photos and the top ten finishers of legendary races.

And when you're looking for the most seminal images from the past half-century of cycling, there's only one person you turn to: Cor Vos, the legendary lensman who has been an up-close eyewitness to the moments that created cycling history.

So that's why we've created the Top Ten collection in partnership with Cor Vos himself, with exclusive licence to use some of the greatest cycling photos ever shot.

Cor's career spans everyone from Merckx through to Pog, so he's got unique insight into how the snapper's role has changed over the years.

Here's Cor himself, in his own words, with an exclusive extract from his forthcoming book, Life Behind The Lens.

From photo roll to editorial in three hours

1977–1980

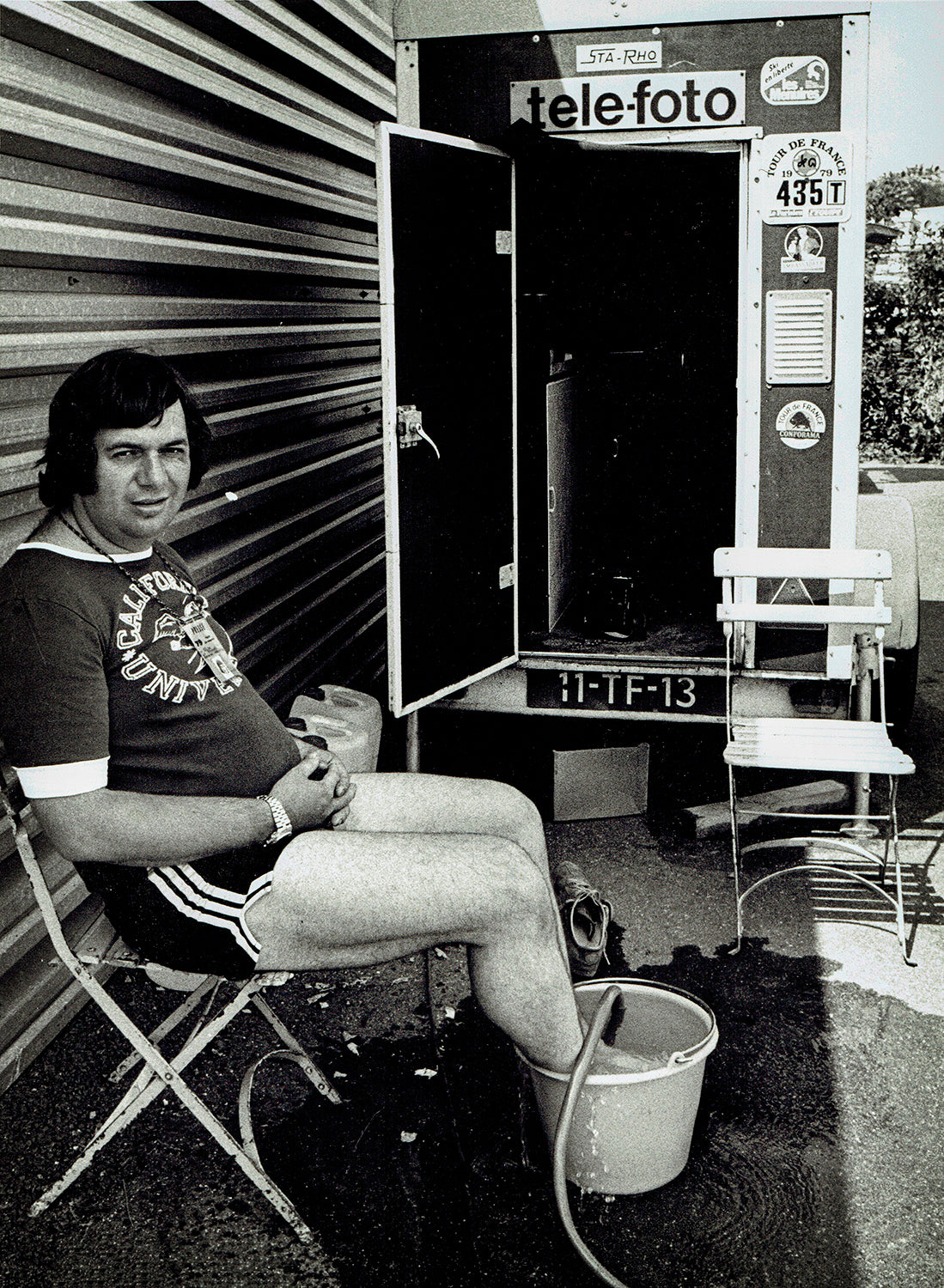

Colour photography had been around for years, but not in the pages of newspapers. That space was reserved for black and white. Not because it looked better – because it was faster. And speed was everything.

As soon as the race ended, the real race began. If I was in Roubaix, the first photos had to be in the Netherlands within three hours. No email, no digital files. Just a roll of film, a darkroom, and a rotary telephone.

Shoot. Drive. Develop. Print. Deliver. Every race required planning down to the minute, because one missed exposure could mean losing the story altogether. What drove me wasn’t just the photo – it was knowing that someone back in Amsterdam or Rotterdam was waiting to build a newspaper around it.

Especially when the race finished in northern Italy. Como to Rotterdam was no trip – it was a mission. No hotel. No break. Just a trailer with a motorbike on the back and the thought of the photo coming out of the tray: this one’s good.

Carla’s courier run.

Early 1980s

While I was in the darkroom, Carla was already preparing the delivery. Twelve envelopes, each labelled for a different newspaper, region, or editorial office.

At midday on Sunday, she set off from Rotterdam. First The Hague. Then Haarlem. Then Amsterdam. Editors knew to expect her – and knew that if the envelope came from Carla, the photos would be good.

From there, she went to the train station to send the next wave of prints to Groningen, Enschede, Maastricht, Heerlen. Dutch Railways were the fastest courier service we had.

Last stop: Dagblad De Stem in Breda. Always the final delivery. Always a smile. Always grateful.

She did this for years. No satnav. No air con. Just a roadmap and the belief that her work mattered. She wasn’t a photographer – not yet – but she was already my partner. The logistical engine behind everything.

“De Hell”.

Early 1980s

Then came the device that changed everything. The Siemens Hell Fernkopierer – we just called it De Hell. It let you send a black-and-white photo through a phone line in seven minutes. A fax for pictures.

You had to tape the print to a rotating drum. It scanned the image like a screw thread and rebuilt it on the other side – assuming the connection didn’t drop halfway through. If the newsroom line was busy, you waited, sweating, as the machine beeped and screeched.

But when it worked? It was magic. Suddenly I wasn’t reliant on trains or cars. I had speed. I could send a photo from the race on the same day. That gave me a serious edge.

It only worked with black-and-white, but that didn’t matter. What mattered was being first.

The horse trailer.

Mid-1980s

One evening at the kitchen table, I said to Carla, “I’ve got an idea.” She looked at me with raised eyebrows. “There go our savings again.”

She wasn’t wrong. I bought an old horse trailer and turned it into a mobile darkroom. Inside went a water tank, chemical trays, an enlarger, and of course, De Hell.

No more waiting for a hotel sink. No more delays. I could develop and transmit within an hour of the finish, even if I was in a dusty car park in northern France or on the edge of a vineyard in Tuscany.

The French laughed at first – “chevaux?” they’d say, pointing to the trailer. Then they saw the prints coming out of their newspapers the next morning. They weren’t laughing then.

It smelled like fixer and sweat. It was cramped, chaotic. But it worked. And it made me faster than anyone else.

The first time I saw my name.

Mid-1980s

Wielersport was the first magazine to credit me by name. Photo: Cor Vos. Just a small line under the image. No capitals. No frills. But to me, it felt like I’d won the Tour de France.

Until then, most photos ran anonymously. Photography was treated like a service – not an authorship. But that changed everything. Riders started to recognise themselves. Sponsors asked for copies. Teams asked for portrait sessions. Doors opened that used to require five phone calls and three faxes.

And I always made sure to shoot more than just the winner. I made sure the rider in 50th place saw his face too. Not because it was sentimental – because that’s what I would’ve wanted.

The windmill.

Mid-1980s

For years, I only shot action. Crashes, sprints, attacks – that’s where the story was. That’s what made the news. Then one day, Carla looked at my contact sheets and said, “Why don’t you ever take portraits?”

I shrugged it off. Something about dynamics. But the thought stuck.

Next race, the peloton passed a windmill. The light was soft. The sky was perfect. I didn’t shoot right away. I waited. Found the composition. Took the photo.

No drama. But it stayed with me. It told a different kind of story. From then on, I saw things differently. Riders at the bus, fans holding signs, mechanics working quietly behind the scenes.

Carla had no training in photography. But she had an instinct for what would last. And that’s the point, really. A good photo doesn’t just capture what’s happening – it captures what remains.

From monochrome to colour.

Late 1980s

Colour came slowly. First to magazines. Then brochures. Eventually newspapers. But it wasn’t just a technical shift – it was a new language.

Black and white was about shape and shadow. Colour was about emotion. The yellow jersey wasn’t just a shade – it meant something.

At first, I carried two cameras: one for slides, one for black and white. Slide film had no margin for error. If you got it wrong, you lost the shot. And I couldn’t develop it myself – I had to send it to a lab and wait. Days, sometimes.

But the demand grew. Sponsors wanted colour. Teams wanted yearbooks. International press wanted atmosphere. I learned to shoot with colour in mind – to see differently.

Eventually, it clicked. The light, the faces, the paint on the road – colour added something else. Something warmer. Not necessarily better. But different. And worth chasing.

The leap to digital.

1990s – Early 2000s

I never thought I’d shoot without film. A camera without a roll felt like a bike without a chain. But by the mid-’90s, digital had arrived – and whether you liked it or not, it was coming fast.

The first cameras were terrible. Bulky. Unreliable. The files were tiny and the colours dull. But the speed… the speed was unmatched.

Editors didn’t want prints anymore. They wanted files – now. Sometimes even before the rider had crossed the line.

I started editing in the back of vans, in press tents, sometimes even on the road. I sent files straight from my laptop, crossing borders with memory cards instead of film.

It wasn’t easy. A lot of good photographers gave up. But I stuck with it. Because deep down, I knew – this is the new darkroom.

Eventually the image quality caught up. Canon released a camera that finally rivalled slide film. I sold the trailer. Bought a camper van. Installed a workstation.

The fixer trays were gone. But the eye? That stayed the same.

Because no matter what’s in your hands – a Leica, a Canon, a laptop – there’s still that moment. That second where everything lines up and you know: this is the shot.